This story originally appeared in Open Source, our weekly newsletter on emerging technology. To get stories like this in your inbox first, subscribe here.

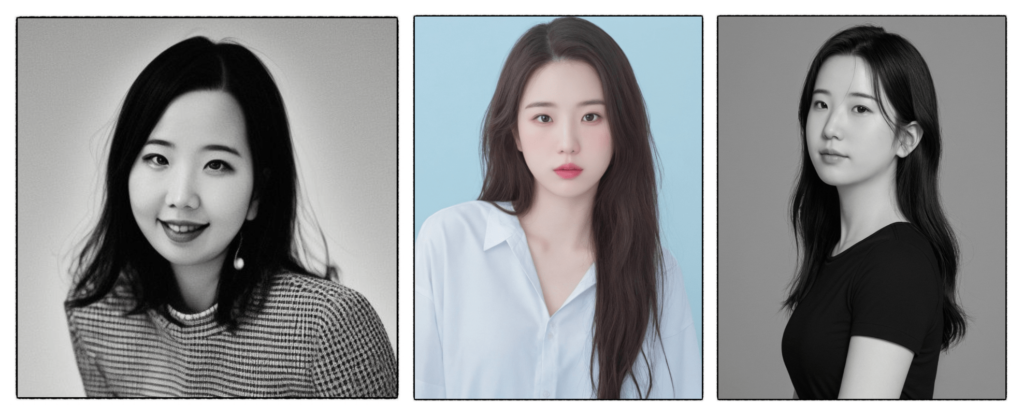

V-shaped face, fair skin, and a slender body—what you see above is the photo of a typical, young South Korean female who meets her nation’s beauty standards.

Except… it isn’t.

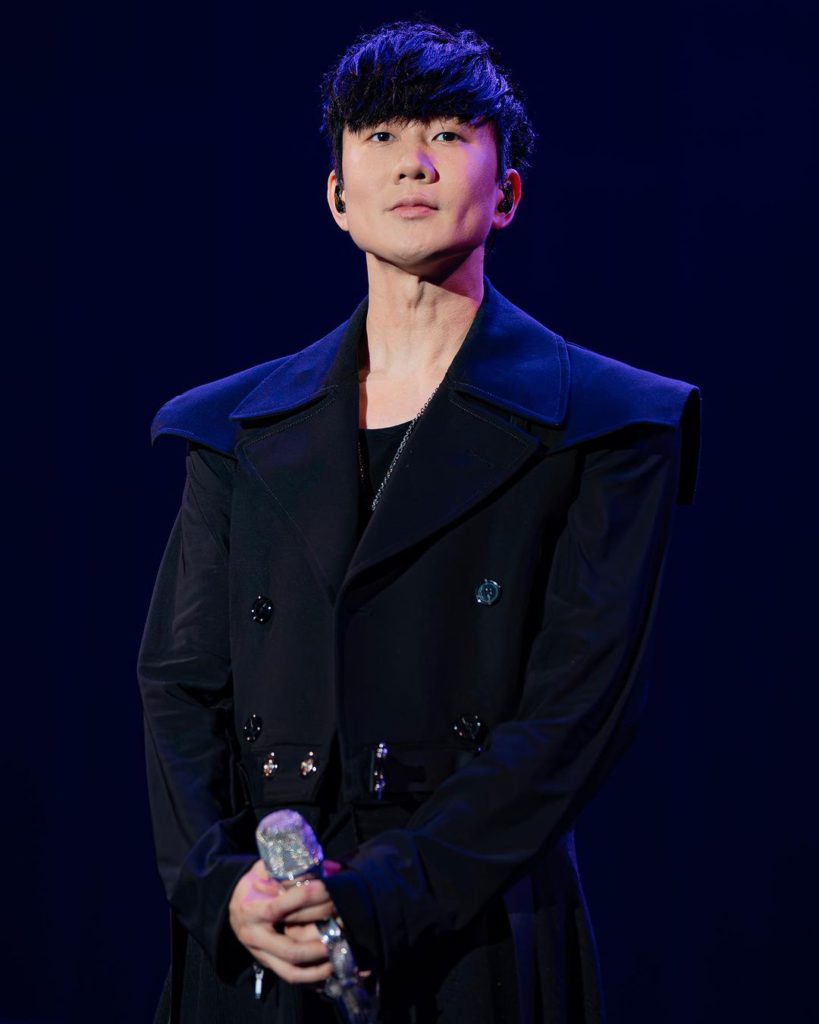

Instead, it’s an artificial intelligence-generated photo of Singaporean singer JJ Lin, who, whilst possessing impressive vocal prowess, is neither South Korean nor female.

In June this year, Lin uploaded an Instagram post comprising a compilation of photos, including the above, putting the mind-boggling capabilities of AI-powered profile photo generators on full display.

While the Lin portrayed in those photos bore some semblance to the actual Lin in real life, you’d hardly fault people for failing to recognize that they are supposed to represent the same person.

Lin’s experience is not an anomaly. Documentations of similar examples have surfaced online in recent months in the form of TikTok videos, blogs, editorials, and more, showcasing the drastic extent to which AI-powered apps modify photos, often beyond the recognition of users.

Most AI-generated profile photos that have appeared on the internet thus far trace back to one primary source: the Snow AI app. It’s developed by South Korea-based app development company Snow Corporation, which is a subsidiary of South Korean internet conglomerate Naver Corporation. In addition to Snow AI, Snow Corporation has also developed photo editing apps such as the B612 app.

Critics have been quick in pointing out that the app, originating from a country known for its idealistic beauty standards, inevitably carries some of these biases, resulting in the excessive nature of the Snow AI app. Yet, even within South Korea, some natives have voiced their reservations about the app, noting that the contrast between their real-life selves and Snow AI’s depiction can be quite stark. As highlighted by Naver blogger Kkoye Couple, while Snow AI offers more realistic outcomes than its older counterparts, these results often fail to resemble the original person.

AI photo generation is big business

But not everyone seemingly shares the same apprehensions about the rise of Snow AI and similar tools.

Despite the widespread discourse surrounding its unrealistic outputs, Snow AI, as of September 12 this year, has been downloaded over 100 million times on the Google Play Store. According to data.ai, the app served around 5.4 million active users between August 27 and September 2, 2023, ranking it as one of the top selfie and beauty editor apps in that period. SensorTower estimates that the app is used in over 100 countries, with most of its current active users hailing from Japan (1.73 million), South Korea (1.27 million), as well as the Philippines (around 526,000) and Indonesia (around 510,000).

According to Korea Joongang Daily, Snow AI generates the bulk of Snow Corporation’s revenue, equivalent to around USD 20 million since the subsidiary was established. Around 90% of the total revenue was generated in 2023, with the AI tool generating around USD 400,000 in August 2023 alone. Kim Nam Sun, CFO of parent company Naver Corporation, explicitly attributed the revenue growth to “the popularity of the AI profile service.”

While recent data indicates that Snow AI’s active user base is gradually dwindling in size, it could be premature to dismiss AI-powered photo generation as a fad.

Since Snow AI’s outputs are generally similar, users have little reason to reuse it after their first try. Instead, they may switch to alternatives such as the LINE super app’s Profile Studio feature or B^Discover, which is developed by Kakao Brain, the AI research arm of Naver’s rival Kakao.

They may also opt to try generative AI tools with broader applications such as OpenAI’s DALL-E 2, Midjourney, Lasco AI, or Karlo. While these tools are not specifically designed for profile photo generation, they can be used to produce similar types of imagery.

More than meets the eye

The popularization of Snow AI also coincides with the increasing use of photos in our lives for a variety of purposes. Profile photos can influence our prospects on dating apps. When inserted into resumes and curricula vitae, they can shape job opportunities and determine likelihoods of career success. In cultures where appearances hold significant value, they may even hold the potential to impact personal relationships and societal judgments. Understandably, having access to picture-perfect photos can offer significant advantages in these areas, among others.

Another factor is usability. Unlike traditional photo editing tools like Adobe Photoshop, which may demand specific skills to achieve desired results, Snow AI is operable with just a few clicks, and the prerequisites are minimal. All a user needs is a compatible smartphone, the ability to make payment, and some patience. (Snow AI takes at least an hour to complete one non-express generation request.)

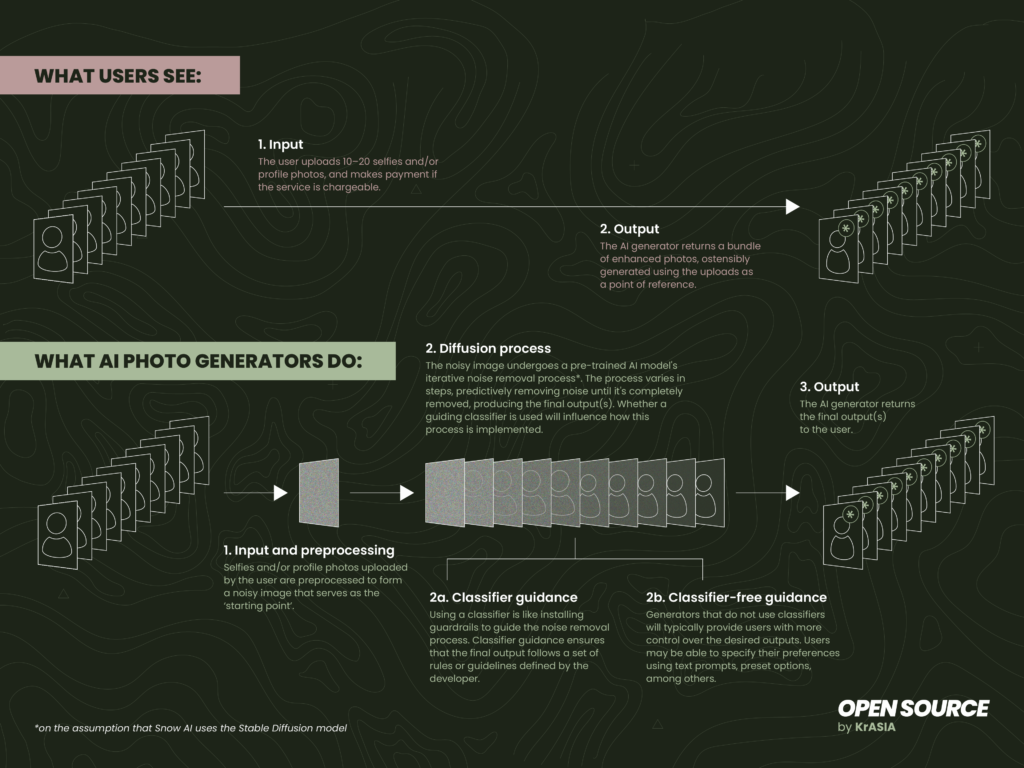

There is, however, a tradeoff. While users can determine which selfies and profile photos to provide to the app as points of reference, they lack visibility and control over the generation process.

Ominous times ahead

AI photo generation is generally harmless when used for fun and by users familiar with the tools. However, as AI technology advances, there’s a risk of AI-generated photos becoming indistinguishable from real ones, blurring the line between reality and perception.

In an era where visual evidence holds significant weight in courts, journalism, public discourse, and beyond, we may reach a point where every photo will need to be met with skepticism. This would diminish the value of photographic truth, affecting processes that rely on photos as evidence of authenticity.

While some may dismiss these concerns as artifice, we’re already seeing instances of this phenomenon unfolding. In South Korea, people are beginning to use Snow AI-generated profile photos for resumes and passport applications, leaving employers and government officials scratching their heads on how best to respond.

Addressing this issue will require developers to be more transparent about how AI-powered photo generators work and the establishment of protocols for reliable identification of AI-generated photos versus real ones. Much of this is, however, easier said than done.

While the world seeks the best way to regulate this technology without losing its benefits, work is already underway to explore multimodal use cases, extending the generative concept to video and motion formats, and potentially even the metaverse. The VeryMe app, developed by South Korean AI startup Lionrocket, enables users to generate photos and videos using a “virtual face” for online platforms like YouTube and TikTok. Another company, Vana, is developing tools to create and personalize the “digital self” for interaction and exploration in the “Vanaverse”, its equivalent of the metaverse.