When Philippine news channel ABS-CBN Online reported that dating platform Sugarbook registered a 60% increase in sign-ups between March and August 2020, the news was met with both amusement and alarm. The news, published in late October, garnered thousands of shares and comments on Facebook, most of them supportive of the pursuit. “Life is hard… we all got to hustle,” someone commented.

If you’re wondering why participation in a dating site is a “hustle,” it’s because, in some ways, it is. Sugarbook prides itself as a dating website for “sugar babies” and “sugar daddies.” The platform matches young females or males with potential partners who are willing to support their companions financially.

Founded in 2017, the platform has been quietly growing its reach across Southeast Asia, after taking off from its headquarters in Malaysia. It’s one of several tech startups that enjoyed a boost thanks to the extended periods of quarantine that led to joblessness and underemployment.

Since August, when the ABS-CBN story broke, the number of Philippine users has even tripled, growing to almost 200,000 by early January 2021, surprising the company. “More users are signing up due to unemployment and the gender pay gap,” Wynette Loo, press representative of Sugarbook told KrASIA.

Data from the Philippine Statistics Authority show that more than 3.8 million are unemployed in the country as of October, 39% of which are women. At the thick of the quarantine in April, the number was almost double that.

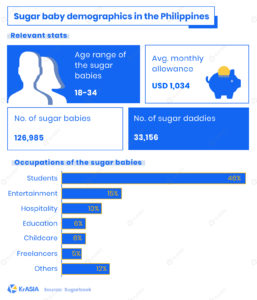

The need for cash might be what drove Filipinos to the service. Sugarbook says that local babies receive an average of PHP 49,000 (USD 1,034) a month from their partners—triple the minimum wage in the capital. Some even get as much as PHP 70,000.

The hefty paychecks come thanks to many moneyed daddies on the service, a fair amount of them Manila-based foreigners from the UK, US, Hong Kong, or Southeast Asia. Loo says that the daddies, who are between 30 and 50 years old, have an average annual income of PHP 1.7 million (USD 35,400). At least 46% of sugar babies in the Philippines are still students.

Users have to be at least 18 years of age and need to sign up with their IDs. Once verified, they can browse for matches and start chatting in a limited capacity. A premium account offers a wider search and unrestricted chat possibilities. But it doesn’t come cheap. A subscription starts at USD 79 a month. Female students who sign up with their school IDs, however, can upgrade to a premium account for free.

Some are worried

The glaring age disparity between babies and daddies is just one in a long list of concerns of women’s advocate groups and human rights organizations. “We know it isn’t prostitution but it could lead to that, and that’s what is concerning,” Nevi Calma of the Philippine Commission on Women told KrASIA.

In December, at the peak of the Christmas rush, PCW released a statement cautioning Filipino women to be wary of “dating sites and e-groups” that involve “money allowances” in exchange for companionship, after news reports of groups on social media platforms encouraging meetups between babies and daddies grew popular.

PLAN International echoes the warning pointing out that women and girls are often abused by people whom they know and trust and that daddies have the power to control or to impose views, needs, and desires, once the females depend on them, explains Mona Mariano, a gender specialist with the organization. “Gender-based violence is not restricted to acts of violence itself, but includes behaviors that are likely resulting in physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering.”

Safer than a bar

Sugarbook responds to this saying that its business model is legal, distancing itself from undesirable activities that may be perpetrated through its platform. “Just like Facebook, Instagram, and every other social network, we have no control over the user’s intentions,” said Loo. “Nevertheless, we constantly educate our members.”

Mark Quintos, a lecturer at De La Salle University’s Behavioral Sciences Department, thinks that Sugarbook may even be a safer “alternative” to other places where “transactional intimate relations” may occur, like in Facebook groups or bars. “The relationship does not necessarily require a physical meet-up,” he said. “The sugarbaby, therefore, can exercise a higher control over the amount of privacy she is willing to give up.”

Still, he isn’t discounting the potentially dangerous arrangements that may arise from platforms like Sugarbook, from the privacy concerns to the possibility of human trafficking in case bad actors take advantage of it.

Where’s my match?

Despite the criticism, Sugarbook aims to expand its user base in the country, targeting 400,000 by year-end. Loo says it’s currently looking to grow its crop of local daddies as only 15% are Philippine-based. The startup is also hunting for matches on its own with potential investors. According to Crunchbase, it so far raised USD 100,000 from angel investors in January 2017. But there are still doubts about the sustainability of its business model. The firm has so far shied away from disclosing the number of its paying subscribers.

Not that Sugarbook minds the scrutiny. The platform seems to be relishing the honeymoon stage of its courtship with users and potential subscribers. “Growth is not just about money,” Loo said. “As long as we’re providing people a platform to build honest and transparent relationships and changing the way people get into relationships—then people will come to learn about us.”