Engines are the de facto heart of an aircraft, directly determining its speed, range, maneuverability, and reliability. Their development spans multiple disciplines, including materials science, aerodynamics, control systems, and combustion technologies. Due to their significant design and manufacturing challenges, high-performance aircraft engines are often regarded as a peak of industrial capability. Currently, only a handful of nations—the US, Russia, the UK, France, and China—possess independent engine development capabilities.

Western countries had an early lead in general aviation, supported by established industry roots and large market sizes. With a century of technical accumulation and policies deregulating low-altitude airspace, companies like Pratt & Whitney, Rolls-Royce, General Electric (GE), and Safran dominate the sector. Among them, CFM International, a joint venture between GE and Safran, holds over half the global market share for commercial engines.

China’s aircraft engine efforts began in the 1950s, initially through reverse engineering due to limited access to foreign technologies. In 2016, the Aero Engine Corporation of China (AECC) was formed to consolidate resources and drive domestic development. This marked the start of a more coordinated push toward self-reliance and local production.

Historically, China’s engine ecosystem grew around military programs. Civil aviation engines developed more slowly and were marked by weaker foundations and significant gaps compared to global leaders, especially in market supply.

Around 2020, demand began to shift. China’s general aviation aircraft market gradually opened, the drone segment grew in scale, and downstream OEM (original equipment manufacturer) shipments increased, driving demand for upstream engines. At the time, only AECC research institutes could supply engines under 1,000 kilowatts for small and midsized drones. Most other domestic companies had yet to scale production. A notable supply gap emerged, paving the way for new entrants, including Falcon Aviation.

Falcon Aviation was founded in 2020 by Xu Keda, a former military officer with two decades of service. During that time, he oversaw dozens of key aerospace procurement and supply chain projects. His experience provided him with a broad understanding of engine technologies, technical roadmaps, and industry dynamics, along with the network and resources to launch a startup. Seeing an opening in the small engine segment, Xu founded Falcon as a focused player in a niche market.

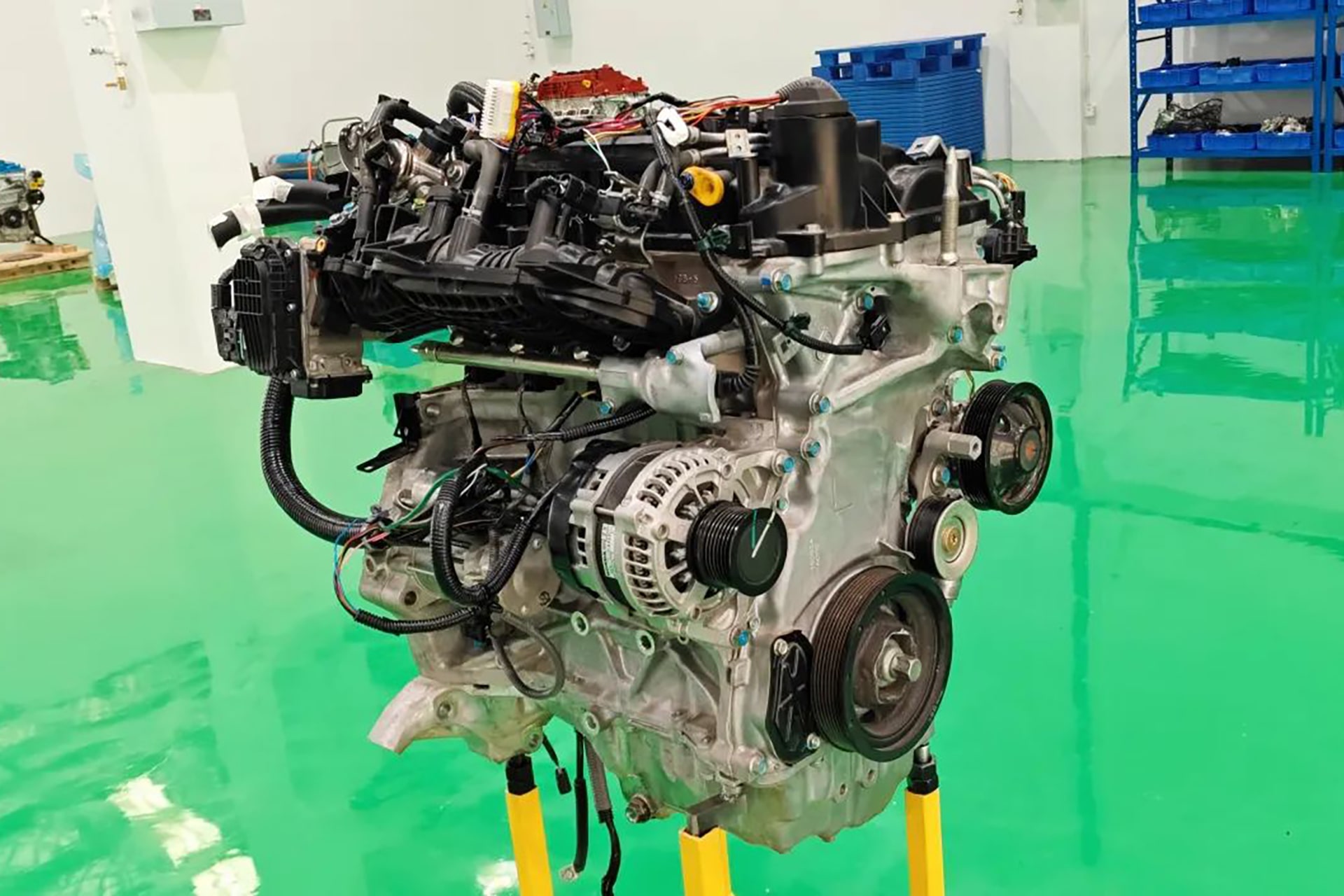

From the beginning, Falcon has concentrated on R&D, production, maintenance, and repair of small and medium-sized aircraft engines. Its mission is to provide airworthy, cost-effective, and domestically controlled propulsion solutions. The company now offers three product lines: piston engines, turboprop engines, and hybrid engines.

Within the piston lineup, Falcon offers four models: the D160 and D180 (heavy fuel), and the G150 and G360 (gasoline-fueled).

The D160 is notable as China’s only heavy-fuel piston aircraft engine certified by the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Priced at about one-third the cost of comparable foreign models, it has accumulated over 100,000 flight hours across platforms such as Yitong’s TP500 and TP1000 and Tuohang’s TF500HS. Falcon is currently pursuing a type certificate (VTC) for the D160.

On the turboprop side, Falcon has introduced the TP360 and TP550, designed as domestic alternatives to imports like Pratt & Whitney’s PT6A. Prototype production is expected this year, with mass production and limited deliveries targeted for 2026.

Hybrid power is Falcon’s bet on the future, given current battery density limitations. With most eVTOL (electric vertical takeoff and landing) batteries below 400 watt-hours per kilogram, Falcon’s TE300 hybrid system uses turboshaft-powered range extenders to achieve four times the endurance of all-electric systems. Mass production is anticipated by year-end.

In under five years, Falcon has expanded from a three-person startup to a team of nearly 200. It operates maintenance and repair centers in Shifang and Changsha, runs R&D in Zhuzhou, and manufactures piston engines in Zhuhai. With a strong product pipeline, the company secured nearly RMB 80 million (USD 11.2 million) in D160 orders by the end of 2024.

Falcon’s success is tied to an unconventional approach. Rather than building everything from scratch, the company partnered with Italy’s DJ using a combination of technology licensing and local manufacturing. This allowed Falcon to establish an EASA-compliant assembly line and domestic supply chain, reducing costs and accelerating market entry. The D160 has now surpassed 300 global deliveries. This model minimized risk and sped up commercialization. Falcon expects 2025 to be a key year for scaled delivery and batch production.

Naturally, the company’s strategy has drawn questions about the “imported” origins of its technology. But Xu remains unfazed.

“Whether it’s from scratch or brought in, the method doesn’t matter. What matters is closing the business loop. Startups should prioritize market needs, not technical elegance,” Xu said. “Make money first. Then, build forward-looking R&D tailored to local platforms and use cases.”

“In terms of first principles, the most important thing for a startup is to reduce costs through technology and dominate the market quickly. Aviation engines may be an industry with high barriers, but competition today is ten times fiercer than five years ago. As long as demand is growing, new players will keep emerging.”

“To survive,” Xu said, “you must be market-driven and airworthiness-focused. In plain terms: cheap and safe. If you can balance both, you’ll live.” Falcon currently has a first-mover advantage in low-cost, airworthy engines. If it masters this niche, Xu believes it could grow into a long-term profit machine.

But the ultimate goal is loftier: to become an engine company centered around control systems, much like Huawei. That means owning the intellectual and engineering core—control systems, combustion theory, simulation modeling—and enabling downstream partners with proprietary tech.

“China has the money, the ability to mobilize resources, a vast domestic market, and a complete, low-cost aerospace supply chain,” Xu said. Just like in electric vehicles, he believes electrified propulsion offers a path for China to leapfrog and even export global standards.

The following transcript has been edited and consolidated for brevity and clarity.

36Kr: Investors and entrepreneurs often fixate on innovation. Many believe everything must be developed in-house from scratch. Falcon’s approach appears different. How do you balance imported technology with internal development?

Xu Keda (XK): A lot of people obsess over whether to import or develop from zero. I think that’s beside the point. It’s just a matter of how the technology is realized. The real goal is to complete the commercial loop.

You might be surprised to learn that the world’s bestselling aircraft are still the Cessna 172 and Piper PA-28, which were designed in the 1960s and mass produced in the 1970s. Hundreds are delivered each year. Why? Because flight schools around the world continue to use them to train novice pilots. Every pilot has to fly one of these small aircraft before progressing to larger ones. It’s a necessary rung on the ladder.

I mention this to say: startup product development shouldn’t be divorced from market needs. Chasing advanced specs for their own sake is pointless. You need to make money first. Then, based on local platforms and use cases, do forward development. There’s a big difference between spec-first and market-first product development. We’ve now shifted firmly to market-first. The only metrics that matter are those grounded in real demand.

36Kr: Is this approach common among Chinese engine startups?

XK: It’s now the norm. If you don’t start with reverse engineering and gradually move toward original development, you won’t survive.

36Kr: Can you share an example of how this approach has influenced Falcon’s market strategy?

XK: Many assume we only make aircraft engines. That’s not true. If there’s market demand, whether on land, in the air, or at sea, we’ll go for it.

We recently delivered a BG360 marine engine for a cargo boat operating on inland lakes. These boats, originally popular with recreational fishermen in North America, carry 20–50 tons of goods through marshy terrain. Annual demand exceeds 2,000 boats, and interest is growing in the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

A US-made version sells for USD 150,000 per boat. Chinese-made ones go for USD 80,000. When you slash the price that much, you need a low-cost engine to match. That’s market demand. Once we spot an opportunity, we immediately pivot and start development.

36Kr: Has this principle also shaped Falcon’s technology roadmap? What are your current R&D priorities?

XK: Absolutely. We base everything on market demand, not what we happen to already have. Right now, we offer piston, turboprop, and hybrid engines. That doesn’t mean we’re limited to just those three. We can do turbojets and turbofans, too. But we’ll only expand when real market demand justifies it.

Lately, I’ve come to believe the most critical part of engine technology is the control system. Falcon might end up becoming a propulsion systems integrator. Sometimes we’ll build our own engine. Other times, we’ll source it. But we must control the combustion theory, simulation, and other core tech internally.

36Kr: There are already many established engine makers in the market. Why is there still room for startups like Falcon?

XK: No matter how big the engine market gets, or how many giants exist, there will always be small players thriving in specific niches.

Take turbojet engines. The French and Czechs led that field early on. Now, Baoding Xuanyun in China has become the world’s top producer of small turbojets, shipping tens of thousands of units annually.

At Falcon, we differentiate by focusing on EASA airworthiness. Low-cost airworthiness is both our tagline and our current priority. No other Chinese engine has earned EASA certification yet. We’re ahead on that front, and that gives us a headstart. If we can dominate this niche, that alone is enough to build a profitable company.

36Kr: Who do you see as Falcon’s benchmark?

XK: No one yet. Our long-term goal is to become a control system-centered engine company. That vision is still rare in the industry. Very few Chinese engine firms both recognize and are capable of doing that.

Look at Seres or Luxeed. Both use Huawei’s control systems at their core. We want to do something similar: control our own systems and empower downstream partners. Huawei enables automakers. We want to enable aircraft developers.

36Kr: What stage is the global engine industry in right now?

XK: Technologically, we’ve hit a bottleneck. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, there was a proliferation of engine architectures. Today’s engine structures are basically the same as they were in the 1960s and 1970s. The only differences lie in component cooling, materials, and manufacturing techniques.

36Kr: What’s the next technological trend in engine development?

XK: Full electrification. It’s not just happening in cars. Aircraft and even marine transport are clearly moving toward electric drive.

For aircraft, electric propulsion has advantages like reduced vibration and easier control. The challenge is: how do you generate that electricity? Batteries? Pistons? Turbines? Hydrogen combustion?

Falcon was one of the first in China to work on turbogenerators. We also built the first engineering prototype. This year and next, we’ll deliver usable products to the market. Battery packs today have energy densities around 200–300 Wh/kg. Our turbogenerator systems can hit around 1,500 Wh/kg. Hybrid piston systems range from 800–1,000 Wh/kg.

36Kr: Given what we’ve seen in EVs, is there a chance Chinese firms could leap ahead in engine electrification?

XK: Very likely. Big firms like Pratt & Whitney, Rolls-Royce, and Safran are thinking about electrification, but Western corporate thinking is rigid. Innovation is slow.

Take a blacksmithing company. They will focus solely on perfecting blacksmithing. They won’t consider entering other fields. That mindset is particularly entrenched in Europe. And if Trump keeps undermining universities and intellectuals, then the next wave of engine electrification might very well start in China.

China has advantages: money, centralized coordination, a massive domestic market, and a mature, low-cost aerospace supply chain. As with EVs, if government support continues, we have the foundation and opportunity to leap ahead and export both products and standards.

36Kr: Where does China currently stand in global engine competitiveness?

XK: Everyone has their strengths. We may not match others on raw technical specs. But in terms of delivery capacity and operational execution, we may be stronger.

It’s like this: Americans write great PowerPoint decks. Chinese firms are better at turning those decks into working products. That’s the difference.

36Kr: For Chinese engine makers to go global, what should they focus on?

XK: First, engines can’t go overseas alone. They have to be bundled with aircraft. You only get traction when the end product goes global.

Second, you need airworthiness certifications. The Federal Aviation Administration and EASA have strict management protocols. If you want to compete globally, you must understand and respect those rules. Certification isn’t just about time, but also about systematic discipline.

Right now, many Chinese drone makers are thriving in underdeveloped areas of Asia, Africa, and Latin America where infrastructure is weak. There’s huge growth potential abroad. If you want to build a large company, you must go global. But it has to be market-driven, not policy-forced.

36Kr: What’s the current level of hype in the engine space?

XK: Very high. Compared to when Falcon started, the competition is now ten times more intense.

36Kr: Building aircraft and engines involves high barriers. What kind of founders can succeed in this space?

XK: The bar is extremely high. Most founders today are former chief engineers from within the system. This space isn’t for just anyone. You need deep resource integration skills, strong project relationships, and significant funding. A small team with just some tech won’t make it. There are plenty of cautionary tales.

Plus, this work is grueling. It often comes at the cost of your health. Many top engineers spend a month or more in remote test sites. This isn’t a glamorous gig where you fly around smoking cigars and pitching investors. Founders who don’t get their hands dirty are doomed to fail.

36Kr: How many startups do you think this market can ultimately support?

XK: The primary player will always be AECC. Startups will fight for the remaining share. I think four or five companies can survive. It really depends on how large the market becomes.

To make it, your company must be market-oriented and airworthiness-driven. Again: cheap and safe. If you can do both, you’ll live.

36Kr: What else do private engine companies need to thrive?

XK: Policy and funding support help. But more than anything, we need patience from the market.

Real support means trust. Give companies the freedom to compete. Let the market decide who wins and loses. That’s the healthiest ecosystem.

36Kr: Falcon is now in its fifth year. Looking back, would you have done anything differently?

XK: I don’t think so. Everyone pays the price for their own perspective.

What we’re doing now may not be entirely right. Only when we’re consistently delivering thousands of engines per year can I say with certainty that we’ve found the right path. But from day one, our team has always been risk-aware.

36Kr: Any advice for aspiring founders?

XK: If you don’t have enough capital and capability, don’t enter this field. It’s brutal. Just having some market insight isn’t enough. This isn’t a casual bet. It is a life-altering gamble. If success were easy, we’d all be billionaires by now.

36Kr: What do you want Falcon to be known for? What kind of company are you building?

XK: Airworthy, low-cost, and domestically controlled.

Our vision is to advance China’s low-altitude aviation sector with domestically produced, airworthy, and cost-effective engines, and to put private Chinese engine firms on the global map.

36Kr: What’s next on your agenda?

XK: In the short term: expand the D-series market share, and ramp up G-series deliveries. Ensure stable operations at the Changsha facility and accelerate MRO center readiness. On the market side, we’ll break reliance on imports, grow our domestic footprint, and boost our global share and influence.

KrASIA Connection features translated and adapted content that was originally published by 36Kr. This article was written by Liu Jingqiong and A Zhi for 36Kr.